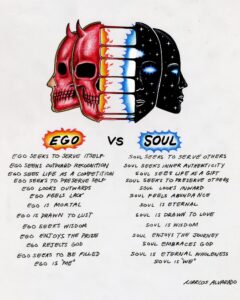

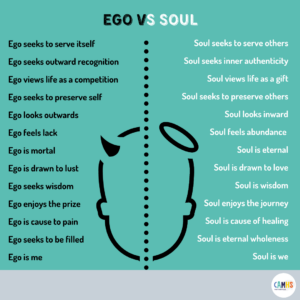

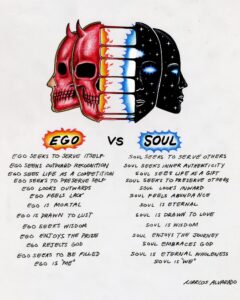

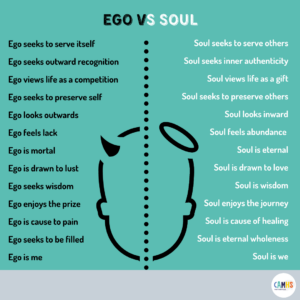

If we seek information online about the ego and the soul, we might see depictions like those below, with the ego demonised in contrast to a pure soul; good versus bad.

Image from: https://camhsprofessionals.co.uk/2021/04/01/ego-vs-soul-%F0%9F%8C%8D/

Image from: https://camhsprofessionals.co.uk/2021/04/01/ego-vs-soul-%F0%9F%8C%8D/

Image from: https://twitter.com/marcosalvarado_/status/1629238900819431424

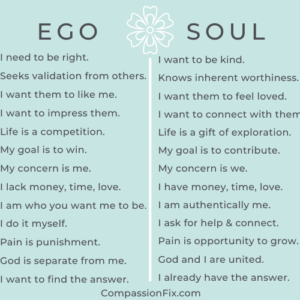

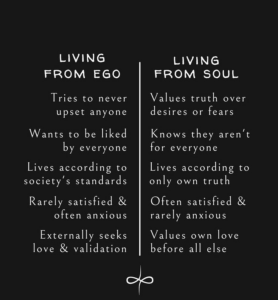

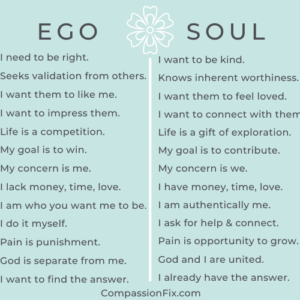

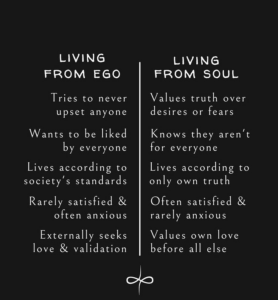

In other depictions, the soul and ego are represented more as polarities on a spectrum, with the soul being the desirable and preferred side, and the ego still reflecting the ‘bad’ less desirable aspect, as in these examplese below.

Image from: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ego-vs-soul-navigating-inner-conflict-self-discovery-growth-bankole

Image from: https://compassionfix.com/practices-main/ego-or-soul

Image from: https://sainttwenty.com/2022/10/03/living-from-ego-vs-soul/

As a general rule of thumb, if something is depicted as good versus bad, it is likely an oversimplification. Both of the above conceptions appear as misrepresentations and misdirections from an important understanding. If we focus on eliminating this ‘bad ego’ and aim to only live from some idealised version of self, the ‘good soul’ self, we miss a more fundamental awareness of our human nature and the potential for integration and healing. We also set ourselves up for failure, as the ego cannot simply be done away with. So if the ego isn’t bad, then what is it? How does it relate to the soul? The explanation below represents a working understanding that helps me in my personal life and practice.

Ego and Soul

For some basic definitions, the soul is the us that we innately are. It is our deepest core self, or core frequency. The ego is the conscious awareness of self and who we perceive ourselves to be. Carl Jung called the ego the ‘centre of the field of consciousness’.[1]

To go a little deeper, ego is a functional aspect of ourselves and is necessary for our existence and operation in physical existence. Our body involves structures that allow our mind to operate and to perceive the world around us. Perception of self is part of our perception of the world; we must have a conception of self in order to function as a person. Ego is, however, something that forms largely during our early years, and the formation process of the ego is not remembered. That aspect is unconscious, such that ego is made up of a conscious ‘I am’ aspect, and an unconscious ego-formation aspect. Hence exists the ego – our self-conceptualisation – neither inherently good nor bad.

The soul is a purely metaphysical aspect of our human self, our deepest aspect. It is the part of human us that is connected to an eternal Us, which may be conceived of as our spirit. It holds our individual blueprint, and represents our highest lifetime potential. The soul can have no presence in this material world without our physical existence, which entails our conscious self-perception. Ego is the reflection of the metaphysical soul in the physical world. Ego and soul are not polarities, nor do they operate on a spectrum. They are both essential facets of human composition.

Why is ego seen as bad?

In a perfect world, our rising conscious awareness as we grow in childhood would be a pure reflection of our soul self. Soul and ego would be aligned such that we would fully embody our soul in the physical world. However we do not live in a perfect world but a human one. Through the formative years of our infancy and early childhood, we learn various information through our experiences, observations and general interactions with the external world. This information becomes a new blueprint, or ‘program’, that effectively comes to overlay that of the soul.

Bruce Lipton, a developmental biologist and author, tells us that our level of consciousness until the age of seven years is at a level below conscious awareness.[2] Our brainwaves are theta frequency in our early childhood, which is equivalent to a state of hypnosis. Is it any wonder that we don’t remember much from these years aside from brief flashes of memory, similar to recollection of our nighttime dreaming state? It is in these years that we learn deeply embedded patterns of thinking and perceiving of parental, and even ancestral, origin. These patterns reflect individual and collective beliefs, expectations and experiences, and can be out of alignment with the soul. Where there is misalignment, we develop metaphysical wounds in our unconscious unconscious ego-formation.

What are wounds?

In essence, wounds are falsehoods, better named as distortions. They are false beliefs that shape our fundamental perception of ourselves and the world by extension. The collection of distortions forms a program, and as our connection to soul filters through this program our ego presents a distorted reflection that we believe as the truth of our self. The ‘bad’ that is popularly conceived is not the ego. It is the version of ego that exists reflecting the ego-formation created through metaphysical distortions. What we then embody, instead of our soul, includes our pattern of distortions.

The distortions might be considered to correlate with Jung’s ‘shadows’. Like the ego they themselves are not inherently bad; they are out of place as part of our self conception and can have a detrimental influence. The deeper they sit in our subconscious, the greater the likelihood of impact. In other words, the less known and recognised our distortions are to our conscious awareness, the less we have the opportunity to recognise and address them, and the more unwanted influence they can have on our lives. The more useful conceptual spectrum, rather than from ego to soul, is instead from an ego out of alignment with soul, to an ego in alignment with soul; a distorted reflection to a true reflection.

It is important to note that distortions are not terrible unrealised aspects of ourselves. They can be positive things that we don’t believe we possess or are allowed, like honest self expression, autonomy, personal power, or even love. In psychoanalysis, along with reference to ‘shadows’ there is also dark versus light. This differs from the dark and light that we may come across in, for example, personality research, where dark denotes a detrimental effect and light denotes a positive effect. In a psychoanalytic perspective, light means what is in conscious awareness, and dark means that which is not in the light of conscious awareness, i.e., the unconscious. When we are unconscious of our soul, it too sits in darkness.

Summary

The ego is our conscious awareness of self and a reflection of our core soul frequency in the physical world. It is only through our conscious awareness that we can know our soul, however what we know as our self is often filtered through distortions that we take on in our early life. If we can remedy this need to think of soul as good and ego as bad, we can start to appreciate the fullness of who we are, why we are as we are, and move towards self acceptance and a healthy integrated state.

About the Author Katie Beckwith

Katie is a psychotherapist at In Positive Health. Working with individuals aged 15 years and older, Katie seeks to enhance a client’s connection with their inner world through client-centred, holistic approaches. Her practice is founded on the delivery of personalised, compassionate, and effective care. Read more about Katie here.

References

- Journal Psyche [Internet] n.d. [cited 8 June 2023]. Available from: https://journalpsyche.org/jungian-model-psyche/

- After Skool. How to reprogram your mind – Dr. Bruce Lipton [Internet]: YouTube; 10 June 2020 [cited 8 June 2023]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e71exrhEBQc

Our speech pathology, psychology and psychotherapy clinic is located in Braddon, ACT, in Canberra’s CBD. Call us on 5117 4890 or email reception@inpositivehealth.com to get in touch.

In Positive Health, Canberra. Nel MacBean Speech Pathologist Canberra. Campbell MacBean Psychologist Canberra.

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra Psychology Canberra psychology Canberra

Image from:

Image from: